On opposite sides of barbed-wire fence, an enduring friendship formed in Scouting

Norman Mineta was a proud 10-year-old Cub Scout in 1942 when the U.S. government began imprisoning Japanese-Americans. Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor months earlier, and Mineta and his family became six of the 120,000 people of Japanese descent interned by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

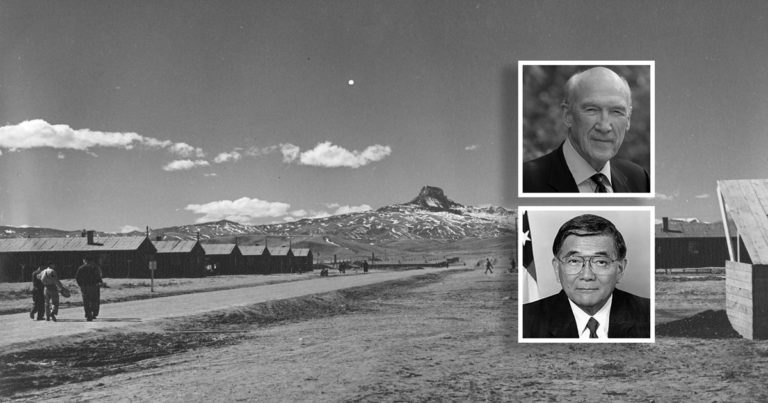

Mineta and his parents, two sisters and brother were moved from San Jose, Calif., to the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Cody, Wyo.

The camp opened 75 years ago this month.

There were no schools for the children at Heart Mountain, so the adults decided to form Boy Scout troops to occupy and educate the kids. Mineta told Boys’ Life in 2002 that the young people played games, read the Boy Scout Handbook and worked on merit badges. (Read the BL story in its entirety at the end of this post.)

As a member of the Heart Mountain Boy Scout troop, Mineta met Alan Simpson, a Boy Scout who lived in Cody. The Cody Scouts traveled to Heart Mountain for a jamboree held inside the camp’s barbed-wire fencing.

Mineta and Simpson became fast friends, bonding over their shared love of comics, silly stories and Scouting.

A year later, when the Minetas were allowed to leave Heart Mountain, Mineta and Simpson remained friends.

Thirty years later, when Mineta was a Democratic representative from California and Simpson a Republican senator from Wyoming, the two remained friends. (Simpson served as a senator for 18 years, and Mineta later became secretary of transportation under President George W. Bush.)

Seven decades after they met, Mineta and Simpson — now both 85 — remain friends. As reported in The Washington Post, the pair returned to Heart Mountain this month to speak out against the racism that led to the camp’s opening.

In his Cub Scout uniform

Long before the days of internment camps, Scouting had deep roots in the Japanese-American community. These families saw Scouting as an American tradition that would teach their children values like citizenship, loyalty and service.

Mineta told Boys’ Life that he wore his Cub Scout uniform when his family boarded that first train headed for the internment camps.

“I was wearing my uniform because the government told all Scouts riding the train to do so,” he told BL. “Only Scouts could move from one car to another. Some families were in separate cars, so we ran notes back and forth as messengers.”

At Heart Mountain, Scout leaders inside the camp wanted to offer the young people some new Scouting experiences. So they contacted Boy Scout troops in the surrounding towns, inviting these local Scouts to join them for a jamboree — a weekend of fellowship and fun we now would call a camporee.

Almost all of them refused, fearful of the unfamiliar faces inside. But Simpson’s leader — “a Scoutmaster ahead of his time,” Simpson said — said yes.

The Scoutmaster, Glenn Livingston, told his guys that the young men inside Heart Mountain camp were just like them. They were Scouts. Simpson, a tad reluctant at first, quickly realized Mr. Livingston was right.

“You knew these were Americans, especially when you met the Scouts,” Simpson told The Washington Post. “They didn’t even know where Japan was.”

As told to Boys’ Life

Read the February 2002 story about Norman Mineta and Alan Simpson below.

And find more content from the Boys’ Life archives in the BL app. Download it by searching “Boys’ Life magazine” in your device’s app store.

On opposite sides of barbed-wire fence, an enduring friendship formed in Scouting